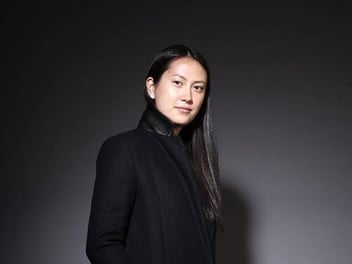

Tilling the Soil and Maximizing Impact: Law Professor James Forman Jr.

James Forman Jr. (Explo Faculty 1986-88) is a clinical professor of law and a supervising attorney at Yale Law School. He is also the co-founder of the Maya Angelou Public Charter School In Washington, DC. Previously, Forman clerked on the Supreme Court for Justice Sandra Day O'Connor. This summer, Forman will be a Scholar in Residence at Explo at Yale. In advance of the Program, Forman spent some time chatting with us about his Explo experience and the features of his career in law and education. Below you will find excerpts from that conversation.

What did you teach when you were an instructor at Explo?

I taught Persuasive Argument Writing and Foreign Policy in the Developing World. I was an undergraduate at Brown at the time and I thought that I knew what I wanted to do. I took a lot of history courses and was very close with my teachers. I know some people criticize the practice of having graduate students teach undergraduate classes, but I loved it. It was like the Explo ideology of teaching—you can really relate to people who are closer to your age. You want to emulate them. So, I wanted to go to graduate school for history. But those same graduate students advised me not to do it!

James Forman Returns to Explo in 2015

James Forman Jr. returns to Explo for the summer of 2015 as part of our Scholars-in-Residence program. Explo at Yale students will be able to attend his talk, meet him in class, debate him during an activity period, and pick his brain at the dinner table. Our residencies offer a unique opportunity for students to engage with top field professionals, and for both students and professionals to learn from one another.

Why do you think your teachers advised you not to go to graduate school for history?

Well, I had developed close relationships with my teachers and they knew my interests and strengths. I was drawn to History because I enjoyed the discussions. And my teachers knew I was very active in campus politics. One said to me, “you seem to like policy and effecting change. You should do go law school.” At the same time, my girlfriend was applying to law school, so I had a good understanding of the process. I decided to do it. The joke is that now I’m the one discouraging people from applying to my field. I tell students all the time not to apply to law school, unless they can really convince me of their reasons.

Why do you discourage students from applying to law school?

I think too many people go to law school for vague and amorphous reasons. They end up unhappy and unfulfilled. I was extremely lucky that in law school I met people who led me to discover what my passion is.

What was that process like—of discovering what you were really interested in doing?

Not as straightforward as you might think! I clerked for the NAACP Defense Fund for two summers during law school and I saw people using the law to create a fairer society. That was how and when I realized you could have a job in law that you were passionate about.

Then I clerked for Sandra Day O’Connor on the Supreme Court and I began to focus on the criminal justice system. I could not believe that people were being put away from 10-20 years in large part because of terrible representation. I mean, I’m talking lawyers that were so bad that a high school moot court student would have done a better job. It dawned on me that criminal justice was the civil rights issue of my era.

What do you mean by that?

Most civil rights activists were focused on education discrimination and housing discrimination. No one was looking at the criminal justice system through a civil rights lens. Now it seems obvious—racial profiling, unequal sentencing, and the disproportionate number of men of color in prison—but at the time, the NAACP Defense Fund, the preeminent civil rights organization in the country, did not even have a criminal advocacy section aside from death penalty cases. This was incredibly compelling and clear to me. When I finished my clerkship, I went to work for the public defender’s office in Washington, DC.

So far this sounds fairly linear. What were the twists?

Well this is when things started to get pretty interesting. I spent a large amount of time in the juvenile court during my first year with the public defender’s office, and it was so clear that poorer kids got tracked out of school quite easily. Some small offense could completely ruin their chance to graduate from high school. The juvenile court judges were mainly decent people, and if you could give them an option besides sending kids to jail they would gladly agree. The problem was there really weren’t good options. We needed to create a good option. I started asking my clients, “What would you want to do if you could do anything? What would be transformative?”

Remember, these are 15-16 year-old kids. These are Explo-aged kids, and I was asking them the same thing that we ask Explo students. Almost all of them said that they wanted jobs. At the time, this felt like startling information. We did not think of these kids as particularly industrious, but these kids wanted work more than anything else.

Wow. So what did you do?

It was crazy. A friend of mine who was an associate at a big DC law firm came to me with an idea for a tutoring program combined with a business. He was going to cash out his 401k plan and buy a pizzeria. The idea was that kids would come to the pizzeria after school, receive two hours of academic tutoring and then—and only then—they could clock in for a shift and get paid. When he told me about it, I wanted to hug him! He had figured out exactly the program I was looking for.

How did it go?

It was quite successful, but we realized right away that two-hour chunks of tutoring was not going to be enough to make a real difference in kids’ lives. We started tossing around the idea of opening a school, and in 1997 we did it. In our first year, there were 20 students and 4 teachers, and the school day ran from 9am to 8pm. Today, The Maya Angelou Public Charter School has two campuses in Washington, DC and in 2007 was awarded a contract from the Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services to run the school in their facility.

How did that happen?

We had relationships with some of the people involved, and our school had been getting good reviews. In the end, the Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services realized that kids had to be in school for at least 7 hours a day, and with us they had an opportunity to make it the best 7 hours of their day.

The school has won numerous awards and has been profiled extensively. It has been a great success. Were you working as a Public Defender through all of this?

I took a leave and then went back but was still very involved with the school. It was hard to want to be in two places at once.

How did you go from those roles to law professor?

Working as a Public Defender and at the school was amazing, and both things pushed me to think about the policies behind the circumstances of my clients and students. Also, being involved at the school and around kids made me start thinking that I would like to teach—it had always been in the back of my mind from my Explo days.

Did something push you over the edge to make the transition?

The unpredictability of my schedule as a Public Defender finally got to me. I was assigned to a murder case on the evening of the first graduation ceremony at our charter school. I was so sad to miss it; I knew all the kids. I had kept in touch with my law school professors, and one offered me a chance to teach a few classes a Michigan Law School on urban education and the war on drugs. This was all stuff I was already thinking about and involved in, but this move would allow me to look at it through an academic lens. I was commuting between Ann Arbor and DC, but I loved it.

So, what’s the takeaway here? How would you advise students or professionals at any age to approach these moments of transition, given what you’ve learned?

My decisions go back to my days in college, sitting around for hours with friends, debating how we could have the most impact. Should we pursue litigation? Legislation? Environmental or death penalty reform? What? The obsessing is a good thing. You are tilling the soil and getting ready.

You have to to be rigorous and do the intellectual work, but when you finally find the right thing, it will be emotional. It will speak to you in your gut and your heart.

Explo was the only teaching experience I had prior to becoming a professor, but it was the most amazing summer job. The students were so involved, and I loved the give-and-take in the classroom. I remember returning to college in the fall and I couldn’t believe that I had spent the summer getting paid to do something so intellectually rewarding. I tell my Yale law students that I am going to ask hard questions, and we are going to listen and learn from one another. Then I tell them something that I figured out at Explo: “I don’t what it’s going to be, but the most interesting thing you hear today won’t be from me, so you really have to listen closely.”