Invent to Learn: How to Tinker, Make + Engineer Your Way to Knowing

A century ago, tinkering, engineering devices, and making things in classrooms was the norm. Today, it's more often than not the exception (but that's changing every day). In their book, Invent to Learn, Sylvia Libow Martinez and Gary Stager want to bring hands-on learning back and offer dozens of ways to help make it happen.

Somehow, between when Angelo Patri wrote those words (1917) and today, education and hands-on tinkering have become two separate things. But in the past few years, as the wonderful book, Invent to Learn: Making, Tinkering, and Engineering in the Classroom, points out, Maker Spaces and Maker Faires have started popping up across the globe. Laser and 3D printers are making their way into more and more schools, and students and their teachers have started approaching how they learn in whole new ways.

Creating a maker space requires time, dedication, and resources, and Invent to Learn is a wonderful guide to help make that happen. Beyond its solid foundation of theory and philosophy, Invent to Learn offers dozens of project ideas as well as a plethora of resources to get you started. Check out the book here.

Create + Design a Maker Space

Here are a few ways you can foster and bring that creative maker culture into the classroom and home. Think of this as a how-to guide on how to help inspire your students and children to learn by doing.

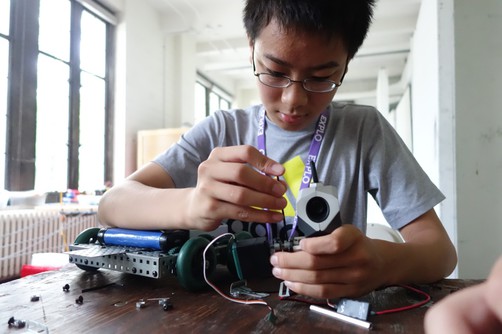

1. Tinkering = Learning

"Making is a way of bringing engineering to young learners," Martinex and Stager write. "Such concrete experiences provide a meaningful context for understanding abstract science and math concepts. For older students, making combines disciplines in ways that enhance the learning process for diverse student populations and opens the doors to unforeseen career paths."

In short, as 19th-century Swiss education reformer Johann Pestalozzi put it, learning should happen with your "heart, head, and hand."

2. Choose Projects that are Substantial, Shareable + Meaningful

To get students interested in hands-on learning, they first need to be curious about what they're doing. Martinez and Stager advise choosing projects that are "substantial, shareable, and personally meaningful," and which can range the length of a class period to the entirety of a semester.

Start with a concrete problem, allow sufficient time for both student exploration and project completion, take a multidisciplinary approach, make the space (and the materials) accessible, and develop projects that foster connection between students and make sure each project is designed for an audience.

3. Lecture Less, Teach Hands-On Learning More

By giving students greater agency over how and what they learn, Martinez and Stager advocate a teaching mantra: "Less Us, More Them." "A robot can deliver curriculum;" Martinez and Stager write, "great teachers provide so much more." What they mean is this: when we give our children instructions on how to do something, they will do it and learn it, but won't venture beyond that point. If, instead, they're asked to do something with no instruction, they'll explore and invent ways to bring that project to completion, often commanding a better grasp of key concepts along the way.

4. Incorporate the Old + the New

Tech is everywhere, but so is cardboard. Think of Minecraft and Caine's Arcade: both are powerful learning tools — digital engineering in one, a cardboard arcade in the other — but exist at opposite ends of the digital-analog spectrum. As Stager and Martinez note, both are powerful resources, and both foster creative learning in their own way. Just like podcasts require developing good writing and oral language skills, project-based learning requires creative thinking, and using all things at your disposal.

5. Design a Maker Learning Space

"Planning a creative design space and collecting the 'stuff' are only part of shaping the learning environment," Stager and Martinez write. "Creating an 'intellectual design space' is another. Your students need to believe they can be inventors and creators."

An ideal space is stress-free, comfortable, and conducive to tinkering, creating, and experimenting. This could involve doors that double as dry-erase boards, furniture that changes shape or purpose as needed, and bins of stuff that are easily accessible. As Andrew Carle, a middle school teacher from Virginia, says, "A maker-space needs to empower visitors and transform them into makers..."

6. Foster Student Leadership

Give students responsibility in maintaining both the space and the materials. Get students to ask one another for help before coming to the teacher (or parent), and foster an environment where they feel comfortable and inspired to share their knowledge and expertise with others. Give them the reins and the space to develop their own leadership styles, and watch them take ownership over their learning experience. They'll not only rise to the occasion, they'll have fun doing it.