The Practicality of Play: A Closer Look

Just how useful is taking time to play? According to Dr. Stuart Brown — and to us here at Explo — very. Here's why:

Aesop's fable about the ant and the grasshopper ends like all classic tales with good triumphing over bad. In this case, the industrious ant is happily satiated come winter, while the grasshopper, who frolicked and sang during the warm months, is dying of hunger when winter comes. The logical conclusion? Play is wasteful when there's work to be done.

But, what if something practical came from the grasshopper's play? What would we conclude then? Could there be more to play than simple amusement? Dr. Stuart Brown — a psychiatrist, clinical researcher, and professor — offers a resounding "Yes!"

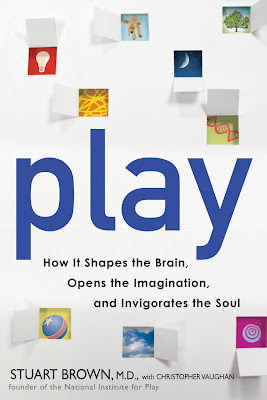

In his new book, Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul, Brown shows that play is not idleness but essential to both productivity and health development. Though it is peppered with stories from his research expeditions and other interesting findings, Brown's book does not read like a science book. Brown summarizes the research conclusions succinctly by explaining that play "shapes the brain and makes animals smarter and more adaptable and consequently promotes survival... [Play] fosters empathy, makes possible complex social groups, [and] lies at the core of creativity."

If play is so important to our lives, shouldn't we know what it is? It's easy to recognize this behavior in a three-year-old building a castle out of blocks. But what does it mean for an 11-year-old, a teenager, or an adult? A problem arises when we assume that if a child is "playing soccer," "playing a video game," or "playing the piano," that this is play. A child at soccer practice is probably not playing by Brown's or other researchers' definitions and, therefore, is not necessarily reaping its cognitive benefits: building new neural pathways, honing higher order thinking skills, and learning to problem solve, to name just a few.

While some parents or teachers may worry that a child might fall behind or miss out on later opportunities if playtime takes the place of more "productive pursuits," Brown offers the moral of his own story: the case of Cal Tech's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Management at this facility (the premier institution in aerospace research for over 70 years) had a big problem in the '90s. They could not find good engineers to replace the retiring generation. Managers described the new hires as "missing something" even though they came from the top universities in the US. Despite the graduates' impeccable academic records and undeniable intelligence, these brilliant scholars were often unable to spot important flaws in complex systems or to solve a problem by breaking it down to its essential elements and rearranging them in new, innovative ways leading to a solution.

After conducting some research, JPL's leaders found that what was missing in their new hires was a past full of tinkering — like taking apart clocks, making pinewood derby cars, or building their own robots and stereos. The older generation of engineers had spent their childhoods doing these things, while many of the newer generation had not. The new engineers were smart and well educated, but they weren't creative thinkers or tinkerers. After this revelation, the main thrust of the interviews of job candidates was questions about their play history and youthful projects. So, the grasshopper... hired!

Some of the most fantastic gadgets on the planet came about from someone's tinkering, and some of the architectural masterpieces started as doodles on a napkin. Someone even discovered electricity while flying a kite. What if these people had been too busy as children — being shuttled from one structured activity to another or doing rote, written exercises from a textbook — to practice imagination and innovation? Brown's research shows that although all work might have been good for the ant, no play has a larger effect than simply making Jack a dull boy.

Review by Cynthia Zwicky, Doctoral Candidate in Education at Tufts University